THE YIDISHE GAUCHOS

Preview

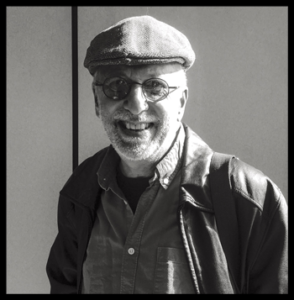

1990 28:00Producer/Director: Mark Freeman

Cinematographer: Mark Freeman

Editor: Mark Freeman

THE YIDISHE GAUCHOS

The Yidishe Gauchos is a story of immigration and survival in a new world. It is a little known story of Jews escaping from Eastern Europe to the pampas of Argentina. At the end of the 19th century millions of Jews fled from persecution and Russian pogroms. Some dreamed of Palestine. Others came to the U.S. and became tailors and peddlers. In Argentina, with the help of the Jewish Colonization Association, thousands became ranchers and farmers. This meeting of Jew and Argentine cowboy created the Jewish Gaucho.

The program includes oral histories, rare archival footage (some never before publicly screened) and comments from Dr. Judith Laikin Elkin, President Latin American Jewish Studies Association and Dr. Haim Avni, Hebrew University Jerusalem).

English and Spanish language versions available.

Teacher’s Discussion Guide

National Center for Jewish Film

Lown Building 102

Brandeis University

Waltham, MA 02254-9110

(781) 736-8600

jewishfilm@brandeis.edu

GOLD APPLE National Educational Film & Video Festival

RED RIBBON American Film and Video Festival

AWARD OF MERIT Latin American Studies Association

SPECIAL AWARD of MERIT MII Users Awards

“The Yidishe Gauchos is an absolute original…. A rare and unexpected glimpse of an unfamiliar

world.” Leo Rosten (The Joys of Yiddish)

“Flamboyant…startling” The Northern California Jewish Bulletin

“Poignant.” The San Francisco Chronicle

“…spellbinding from start to finish.” Jewish Week

“There’s nothing like The Yidishe Gauchos…I enthusiastically recommend it.” Deborah Kaufman, (Former) Director, The San Francisco Jewish Film Festival

WATCHING THE DETECTIVES: Four Views of Immigrant Life in Latin America

Jeff H. Lesser Connecticut College

Latin American Research Review, Vol. 27, No. 1 (1992), pp. 231-244

… Mark Freeman’s The Yidishe Gauchos, an examination of immigrant life on Argentina’s Jewish agricultural colonies, is perhaps the most sophisticated film of the four examined for this essay. A filmmaker from San Francisco, Freeman conceived and completed the project while accompanying his wife, political scientist Alison Brysk, on a year-long research trip to Argentina. The Yidishe Gauchos was clearly made by a professional artist. The sense of film and filmic techniques is always apparent in the constant interplay among live action, still photographs, historical footage, overlapping maps, and music. Actor Eli Wallach’s narration makes this documentary a pleasure to listen to. The Yidishe Gauchos is extremely comfortable for academic viewers because the shifts from past to present are completed with ease. Freeman is also a good detective. He has collected photographs and films from colonists and their descendants, including an original film made by an agricultural engineer in Argentina. Freeman’s own ability to speak Spanish meant that he was not forced to rely on English speakers for his oral histories. The subtitling is also excellent, with even Yiddish-language songs subtitled. The Yidishe Gauchos thus permits the audience to know individuals as well as their social surroundings in an aural and visual sense.

The Yidishe Gauchos begins with a short history of Jewish immigration to Argentina, including a map of South America with Argentina highlighted for those who know nothing of the region. The “Teacher’s Discussion Guide” written to supplement the film is also useful in this regard. The documentary focuses on the Jewish agricultural colony of Moisesville, founded in 1889. In 1891 Moisesville became part of the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA), which was established by the Baron Maurice de Hirsch, according to the film, to create “a new way of life for Jews as farmers on the South American frontier.” The actual goals of the JCA and de Hirsch were neither so noble nor so simple. A major motivation for sending Jewish colonists to Latin America was to keep Eastern European Jews from relocating in Western Europe, where they might damage the status of established Jewish communities. 9 For example, the original articles of association of the JCA explicitly state that Jews would be settled “in various parts of the world except in Europe.” 10 Although these non-philanthropic motives for the creation and work of the JCA have been well documented, The Yidishe Gauchos never mentions them. The documentary does contain a virtual advertisement for the work of the JCA in Israel today. This section seems entirely out of place, even though the credits indicate that the foundation linked to the JCA even though the credits indicate that the foundation linked to the JCA helped fund the production.

Like most documentaries, The Yidishe Gauchos starts at the beginning. An elderly resident of Moisesville describes a pogrom in Eastern Europe, thus establishing one important motive for emigration. Judith Laiken Elkin, a historian of the Latin American Jewish experience, briefly describes the JCA’s decision to establish colonies in Argentina. Haim Avni, of Hebrew University’s Institute of Contemporary Jewry, is also interviewed and by interspersing the comments of academics with those of elderly members of the community, Moisesville is soon brought to life on the screen. In 1925 the town had thirty-three thousand Jewish inhabitants, and this is the era that the The Yidishe Gauchos presents.

Freeman’s film tries to give the viewer a sense of the difference between the Jewish immigrant farmers and their neighboring Gentile gauchos, described famously by Domingo Sarmiento as uneducated “with ill-understood facts of nature, and with superstitions and vulgar traditions.”11 The Jewish colonists, in contrast, were almost universally literate, and more Yiddish dailies were published in Argentina than in the state of New York. The colony’s library of ten thousand volumes was undoubtedly an oddity on the pampas. Yiddish theater productions, with New York’s biggest stars, usually made their first Argentine (and South American) stop in Moisesville. It is not surprising that Moisesville was referred to by its inhabitants as “Idischelohnd” (“Jewish country” or “the land of the Jews”) and that Yiddish songs celebrated that “the Messiah has already come to a little corner of Argentina.”

This strong sense of being Jewish, which eighty-five-year-old Taibe Trumper describes as “a totally Jewish way of life,” has not continued. Freeman cleverly moves from past to present by interspersing comments and footage from “the Jerusalem of Argentina” with interviews of those who note not so sadly that their children today speak only a few words of Yiddish. One resident reminisces that “it was different then,” fondly remembering that the first generation born in Argentina wore the same wide chaps and leather boots as the “real” gauchos even though “they spoke perfect Yiddish.”

The celebratory tone of The Yidishe Gauchos begins to diminish in the second half of the film. Discussions of crop failure due to weather, locusts, and the economic policies of the JCA are presented at length. Natalio Guiger, the eighty-two-year-old former manager of Moisesville’s agricultural cooperative, complains that the Jewish colonists “were like slaves to commercial interests.” Freeman points out, however, that while Jews in Moisesville might have been afraid of losing their land, the 1919 Semana Tragica showed that those in Buenos Aires “were in danger of losing their lives.” Nevertheless, by the 1940s, more Jews were leaving the colony than arriving; and by the end of World War II, the Jewish colonial experience had virtually ended.

Ultimately, The Yidishe Gauchos is about people, and one of the most valuable aspects of this documentary is the frequent personalizing of the colony’s history. An interview with eighty-two-year-old Professor Maximo Yagupsky is interspersed with footage from town weddings, and one almost feels as if social history should never be written, only viewed. An interview on preparing wedding food with Doicha Winer, for whom “food always comes first,” led one viewer of The Yidishe Gauchos to consider bringing Winer to the United States to bake the strudel for her daughter’s bat mitzvah. In these scenes, the strength of the documentary comes through, and viewers of The Yidishe Gauchos, especially students, will better understand Latin America and the history of its immigrant groups after seeing it….

9. See Elkin, Jews of the Latin American Republics; Haim Avni, Argentina y la historia de la inmigracion judi(a, 1810-1950 (Jerusalem: Editorial Universitaria Magnes, 1983); James Scobie, Revolution on the Pampas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964); S. Adler-Rudell, “Moritz Baron Hirsch,” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 8 (New York: Leo Baeck Institute, 1963); and Jeff Lesser, “Pawns of the Powerful: Jewish Immigration to Brazil, 1904-1945,” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1989. 10. Memorandum and Articles of Association of the Jewish Colonization Association of September 19, 1891 (London: Jewish Colonization Association, 1891). 11. Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Life in the Argentine Republic in the Days of the Tyrants; Or, Civilization and Barbarism (New York: Hafner, 1970), 28. 236REVIEW ESSAYS l)

‘Yidishe Gauchos’ To Ride Again Sept. 9

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO – If you haven’t seen something before, it is new to you, no matter how old it is. That’s the thinking behind Yiddishland scheduling a Sept. 9 showing and discussion by Mark Freeman of his 1989 half-hour-long documentary, The Yidishe Gauchos, at a private residence on Mt. Soledad.

The occasion is a fundraiser for Yiddishland, which makes its headquarters in La Jolla Village. People who register prior to August 31 will pay only $20. Not only will they see the movie, they will also schmooze with Freeman who is an emeritus professor of theatre, television and film at San Diego State University, and with Prof. Alejandro Meter, a University of San Diego professor whose academic specialty is the Jewish experience in Latin America.

After August 31, the price goes up with the longer you wait, the more you pay. Between Aug. 31 and Sept. 6, the ticket costs $40; and after Sept. 6, it’s $50. Those who prefer to see the movie and hear the discussion on Zoom can do so for $10 prior to Sept. 6 and for $18 afterwards. One may register via the Yiddishland website.

The Yidishe Gauchos is an exceptionally well-edited, finely-crafted film narrated by the late, great, actor Eli Wallach (1915-2014). It incorporates historic film footage with interviews with octogenarians and septuagenarians who lived through many of the experiences described in the film. These ranged from the Russian pogroms that impelled Jewish migration to Argentina in 1890 through developments over the next 10 decades.

Aron Rais, who was 80 when the film was made, described one pogrom from which he by chance escaped: “People were being killed with knives, not bullets. It was horrible. They brought them to the cemetery, made a ditch 300 to 400 meters long and put all the bodies in.”

Initially, the Russian Jews settled in Buenos Aires, but Baron Mauricio de Hirsch (1831-1896), the founder of the famed Orient Express, created the Jewish Colonization Association, financing colonists who wanted to become farmers. University of Michigan Prof. Judith Laikin Elkin, who at the time of the documentary was president of the Latin American Jewish Studies Association, said that the German Jewish baron believed “that Jews had been separated from the land for too long” and that “it was necessary for Jews to go back to the land and reestablish roots in the real world.”

Initially, gauchos who were descendants of Spanish settlers and indigenous Argentines were wary of the Jewish settlers, with misunderstandings sometimes ending in a gaucho fatally knifing a Yiddish-speaking settler. Later, however, noted Celia Jruz, 77, said “We all know each other, and we are friends. People aren’t afraid of the gauchos like before.” Leon Borodovsky, 81, agreed. Indicating a man beside him named Rodriguez, Borodovsky said, “He is part of our family. He has been with us for 60 years” and taught the Borodovsky family about living in Argentina.

The Jewish Colonization Association gave pioneers about 200 acres, a small house, a few cows and some chickens, along with a healthy mortgage that the association was very insistent be paid on time, or else the colonists would face eviction. That was bearable in good times, but when adverse weather conditions or locusts plagued the farmlands, wiping out everything, creditors including the Jewish Colonization Association were unsympathetic. Either the colonists must pay or move out.

While there were numerous Jewish farming communities in the contiguous provinces of Buenos Aires, Entre Rios, and Santa Fe, the bulk of Freeman’s documentary focused on the picturesquely named Moises Ville (Moses Town), where for decades Yiddish culture flourished. “There were three Yiddish dailies, more than there were in New York at the time,” Elkin commented. “There were periodicals, literary reviews, a very, very vibrant life going on in Yiddish culture.” The Kadima was the local Yiddish theatre, often a preliminary stop for touring Yiddish actors like Maurice Schwartz before bringing a production to Buenos Aires.

Wallach noted that “Moises Ville’s two libraries had 10,000 volumes in Yiddish, Hebrew and Spanish. The Jews had a fever to read and to learn. The Jewish Colonization Association built and staffed about 70 schools. Illiteracy, which was as high as 65 percent among other immigrant groups, was virtually unknown in the Jewish colonies.”

While Yiddish learning was treasured, some Argentine customs were assimilated by the Jewish colonists. For example, the drinking of a brew made from maté was popular. The children of the colonists grew up wanting to imitate the gauchos’ sartorial style. “They had to have the right clothes and a scarf, wide pants, a hat and boots,” one woman recollected. And, “having a horse was like having a new car.”

With literacy comes knowledge, and the colonists put that maxim to work in the field of agriculture. Said Wallach: “Jews were the first to breed milk cows and create commercial dairies. They introduced new crops to Argentina. With 2 percent of the cultivated land, Jews contributed 7 percent of the total agricultural production.”

Most colonists, who needed to sell at a good price the produce of their small farms, felt that they were exploited by merchants, who wanted to buy everything cheaply. Natalio Giguer, 82, asserted that “the families of the colonies were slaves to commercial interests” at least until they formed a cooperative, of which he served as manager. He said the colonists came to understand that “the co-op was their second home.” Administrators of the Jewish Colonization Association also could be high-handed with the colonists, Giguer said.

Agreeing, Elkin said that the JCA “told them what to plant; they told them when to plant, they gave them a certain amount of assistance but no more.” Added Giguer: “The co-op fought hard to defend the colonists. I personally tried to save them from eviction, but I couldn’t.”

However tough it was for farmers in the Jewish colonies, the situation in Buenos Aires in January 1919 was far tougher. This was the time of the only recorded pogrom in the Western Hemisphere. Jews were accused of starting a general strike, which was likened to the Bolshevik, Communist tactics of the recent Russian Revolution. “Afraid that the same thing would happen here, the Silver Shirts, as they were called, all ran wild in the streets, killed a number of Jews, maimed others,” Elkin stated. “There was rape and looting and all the rest of those things.”

Freeman’s documentary portrayed happier times in the colonies including a wedding, a brit milah, and the feasts that accompanied such events. Commented Doicha Winer: “For us Jews, nothing happens without food. … For dessert, there’s strudel with nuts and honey. This is a typical wedding dessert. Not everyone knows how to make it. My grandparents and my mother made it. Now it’s my turn. I’ve already taught my daughters.”

The fortunes of the Jewish colonies started to wane, ironically as a result of the policies of the organization that had helped them to begin in the first place. The Jewish Colonization Association decided that land grants would not be made to the children of colonists (of which typically there were six or seven per family) but instead would be reserved for new immigrants. As a result, families were separated, with the grown children seeking work in the big cities and not returning to the colonies. Meanwhile, the number of immigrants dwindled with the last group of 180 families from Hitler’s Germany arriving in 1933.

Coupled with the development of big, mechanized farms with which the little farmers could not compete, towns like Moises Ville suffered huge declines in population. The synagogues, libraries, and theaters were vacated. Elkin suggested this was not necessarily a failure because many ofthe children of the farmers who moved to the cities became professionals. She likened the colonies to “cocoons from which the butterflies have fled into a very constructive, lively, intellectual life in the cities, so I regard them as very successful.”

Wallach quoted a saying of the former colonists: “We planted wheat and grew doctors.”

Today, there are a few Jews following the Jewish way of life. “Mostly they just keep an eye on things,” Wallach said. “As they say here on the pampas, ‘the eye of the owner fattens the cattle.’”

The documentary includes clips of Yiddish and Spanish songs, and, yet through some very tight editing, is able to convincingly cover a century of history in just 30 minutes.

Donald H. Harrison is editor emeritus of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com

1st International Conference on Ethnological Cinema (Spain)

American Anthropology Association

American Film and Video Festival

Anthropology Film Center (Santa Fe, New Mexico)

Claremont Colleges

Film Arts Festival (San Francisco)

International Hispanic Film Festival

Judah L. Magnes Museum — traveling exhibition

Jewish Broadcasting Network

Jewish Film Festival (Britain)

Jewish Museum of Maryland

KQED Jewish Film Festival

KTEH

Latin American Studies Association

Margaret Mead Festival

Melbourne International Film Festival

MUBI

Museum of Modern Art New York National Educational Film & Video Festival

NM State History Society

Parnu International Visual Anthropology Center (Estonia)

SDSU, Lipinsky Institute

Shalom TV

Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of Natural History

Stanford University

WTTW Image Union

University of Judaism

Yiddishland (La Jolla, CA)

Production History

I lived in Buenos Aires for a year (1988) with my wife, Alison Brysk. (She was doing fieldwork for her book The Politics of Human Rights in Argentina.) It was a great relief for us to travel to the countryside—even on overnight busses. My family’s stories of immigration to the New World of Philadelphia and Chicago would seem to have little in common with those of Jewish ranchers and farmers on the Argentine pampas. But watching dough stretched across a kitchen table in Entre Rios brought me back to my great-grandmother Ella’s streudal extravaganzas. The stories I heard from the 70 and 80 year-old children of the Yidishe pioneers resonated for me. It seems to me that history is made and lived by each of us in our daily lives. And now more than ever we have the tools and opportunity to preserve and learn from our heritage. I always marveled at the shoeboxes full of photos that I was offered. They were treasure-troves. But all too often the names, dates, places and events depicted were lost to living memory. (I now compulsively label all my family snapshots. But I wonder how many digital images will be accessible 100 years from now.)

One of the pleasures of making the Yidishe Gauchos was working with Eli Wallach to record the narration. He was wonderfully generous. I directed the recording session by telephone, because I didn’t have a budget to travel to New York from my studio in San Francisco. It was such a pleasure to hear him give life to our simple script. (For me this was a much richer experience than the time Robert Redford agreed to do a voice-over on his own, if I’d just mail him the script.)

The documentary was completed and a copy in Spanish sent to Argentina in time for the hundredth anniversary of the founding of Moisesville, the first Jewish colony in Argentina. There is often so much more material discovered than can be included in a short film. I was especially pleased to be able to curate an exhibition of historic photographs to accompany the video at the Judah L. Magnes Museum in Berkeley, California.

Links

Fiddler on the Hoof: The Jewish Gauchos of Argentina

Adventures on the Pampas: Or How I Won the Small Format War

Yiddish Gauchos???

3 Interviews with Mark Freeman

Bay Sunday

Below San Francisco with Bonnie Burt

El Almanecer

Archives

American Jewish Archives

Dana Herman, Ph.D.

Associate DirectorThe Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives

3101 Clifton Ave.

Cincinnati, OH 45220

(513) 487-3069 Extension 3369

dherman@huc.edu

UCLA Film and Televison Archive

American Archive of Public Television